This text was written as a replacement for a lecture I was scheduled to give, but was unable to because of other issues, on a module on The Psychology of War and Peace at Sheffield Hallam University. March 2020

One starting point in considering oppression and cruelty in many psychology courses is to look at studies which have constructed situations in which people end up behaving in cruel and oppressive ways, such as Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram’s study of obedience. There is a psychology of oppression & cruelty but there’s more to human behaviour in crisis than the cruel and neglectful, and it’s important to try to construct a psychology of resistance to oppression and cruelty. Both Milgram and Zimbardo were well aware of this, which is apparent if you read their own accounts of their research (Milgram 1974, Zimbardo 2007), rather than the condensed textbook versions.

This essay will describe a number of case studies of people who, in various ways, did the right thing in evil situations, and then try to disentangle aspects of motivation, situation or personality which might have been important in their resistance.

In fact, many of Milgram’s own respondents successfully resisted the pressures of the experiment. Milgram ran very many versions of the shock experiment, and in most of them people resisted at much higher levels than the 32% in the version usually cited. He was interested in what factors would allow people to resist the commands of the experiment, and he found many, so that there were many conditions (where the ‘experimenter’ isn’t physically present, where there is a ‘fellow teacher’ who resists the ‘experimenter’, where there are two ‘experimenters’ who quarrel, and so on) where obedience was very low. Even in the standard version, there were many who resisted. There is a video of such a person at 13:44–15:55 in this video https://vimeopro.com/celialowenstein/portraits/video/110417804

Milgram was rightly interested in these resisters, I’ll discuss his account of them later on.

Recently, Zimbardo has moved into explicitly dealing with ‘heroism’ (though he later questioned whether ‘hero’ was the best word) as in Franco, Blau & Zimbardo (2011).

Franco et al develop a typology of ‘heroes’, ranging from those who face physical peril, whether military or civilian, to those who show social sacrifice: good Samaritans, bureaucracy heroes, or whistleblowers (also religious and political figures, martyrs, political or military leaders, adventurers, scientific heroes, underdogs). They found that the public view favoured physical peril as being heroic, and compared with physical risk, “social courageousness items were marked as heroic less frequently, showed greater overlap with altruism and were frequently viewed as being motivated by neither heroic nor altruistic intentions” Franco, Blau & Zimbardo 2011, p8

You can see Zimbardo talking about this project and his ‘Hero Construction Company’ in a 2012 interview at http://vimeo.com/40425064. The section I use in the lecture runs from 6:44 to 9:02. Another part of the interview will be referenced later.

Some examples

It’s important to remember that at all times, in all places, there are people who stand up for doing the right thing. Historically, many of them end up being recorded as martyrs, unfortunately, but that can be the way heroism goes. Here is a quick run-through of some examples, arranged chronologically. I will come back to some of them in more detail in trying to give a psychological account.

Slavery-era USA: I came across a nice example in a reprinted collection of papers from the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, published in The Underground Railroad (Still, 2017). The Committee was part of the ‘Underground Railroad’, which was a network in the early and mid-19th century which helped to organise the escape of slaves from the southern states of the U.S.A. to the free states in the North. This was a serious crime in the southern states, and even if they reached the North, slaves were vulnerable to being kidnapped, legally or otherwise, back into slavery. Still records that in 1856 a police officer from the Mayor’s Force turned up at their office at a time when they were expecting a party of escapers to arrive, which caused them great alarm, but he told them:

“I have just received a telegraphic despatch from a slaveholder living in Maryland, informing me that six slaves had escaped from him, and that he had reason to believe that they were on their way to Philadelphia, and would come in the regular train direct from Harrisburg; furthermore I am requested to be at the depot on the arrival of the train to arrest the whole party, for whom a reward of $1,300 [a very large amount of money in 1856: slaves were valuable possessions] is offered.

Now I am not the man for this business. I would have nothing to do with the contemptible work of arresting fugitives. I’d rather help them off. What I am telling you is confidential. My object in coming to the office is simply to notify the Vigilance Committee so that they may be on the look-out for them at the depot this evening and get them out of danger as soon as possible. This is the way I feel about them; but I shall telegraph back that I will be on the look-out.” Still 2017, p246

This probably risked his job, and maybe prosecution. Good work, un-named police officer.

World War One: Not all soldiers are prepared to follow orders to kill. Harry Patch was one of the longest-surviving soldiers from World War One. He was a member of a machine-gun team, a main mechanism for delivering death, but he wrote in his memoir:

World War One: Not all soldiers are prepared to follow orders to kill. Harry Patch was one of the longest-surviving soldiers from World War One. He was a member of a machine-gun team, a main mechanism for delivering death, but he wrote in his memoir:

“The team was very close-knit and it had a pact. It was this: Bob said we wouldn’t kill, not if we could help it. He said ‘we fire short, have them in the legs, or fire over their heads, but not to kill, unless it’s them or us.’” Patch, 2007, p71

Early stages of the Holocaust: Paul Grüninger (Paul Groeninger in some English-language versions), was a Chief of Police on part of the Swiss border with Austria in 1938-39. After the Nazi occupation of Austria in March, 1938, the Swiss government decided to prevent the movement into Switzerland of Jewish refugees. They cited concerns about the risks of ‘overload’ of refugees/asylum seekers, foreigners who would have difficulty integrating. There was fear of foreign ‘overpopulation’ in a small country. Refugees were depicted as ‘rejects, the dregs of society’.

Early stages of the Holocaust: Paul Grüninger (Paul Groeninger in some English-language versions), was a Chief of Police on part of the Swiss border with Austria in 1938-39. After the Nazi occupation of Austria in March, 1938, the Swiss government decided to prevent the movement into Switzerland of Jewish refugees. They cited concerns about the risks of ‘overload’ of refugees/asylum seekers, foreigners who would have difficulty integrating. There was fear of foreign ‘overpopulation’ in a small country. Refugees were depicted as ‘rejects, the dregs of society’.

This reasoning might sound familiar to you.

In April, 1938 border guards were ordered to refuse entry to those crossing from Austria without an entry visa. Grüninger and his staff ignored these commands, and used several strategies to admit Jews ‘legally’, as well as illegally. They allowed 2-3,000 refugees into Switzerland. In April, 1939, he was suspended from duty. In 1940 he was convicted of allowing refugees to enter Switzerland illegally. He was dismissed and lost his pension and all other public employee privileges. He died in poverty in 1972. He was pardoned posthumously in 1995 (Rochat & Modigliani, 2000)

He later said of his motivation

“…we did not have the heart simply to send the refugees back and, who knows, perhaps even to condemn to death people who had been mistreated in the most shameful way in Germany […] we were guided also by the opinion of a large portion of the Swiss people, of the press, and of the political parties.” Rochat & Modigliani, 2000, p99

Later: From 1935 to 1943 Irena Sendler or Irena Sendlerowa worked for the Department of Social Welfare and Public Health of the City of Warsaw.

Later: From 1935 to 1943 Irena Sendler or Irena Sendlerowa worked for the Department of Social Welfare and Public Health of the City of Warsaw.

She also pursued informal, and during the war conspiratorial, activities, such as rescuing Jews, primarily as part of the network of workers and volunteers from that department, mostly women. Sendler participated, with dozens of others, in smuggling Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto and then provided them with false identity documents and shelter with willing Polish families or in orphanages and other care facilities, including Catholic run convents, saving those children from the Holocaust. Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irena_Sendler

There were a few options available. The first route led through the underground corridors of the courts in Leszno. Anonymous janitors were bribed. But what if the exit on the Aryan side was closed off?

The trolley tracks were the second route – Irena could count on the help of a tram driver she’d befriended, Leon Szeszko. The third option was to walk out together with the worker brigades. […] Route number four was the ambulance leaving the ghetto. Infants were carried across in crates and sacks. […] A loudly barking dog was bought so as to obscure the crying of babies. Irena Sendlerowa would bridle at being called a heroine, so let us call her a social activist. She saved 2,500 Jewish children. Not by herself, as she always emphasised. During the war and the time of the occupation, she dreamt of having dry shoes. Her interests were politics, history, and people. Culture.pl https://culture.pl/en/artist/irena-sendlerowa

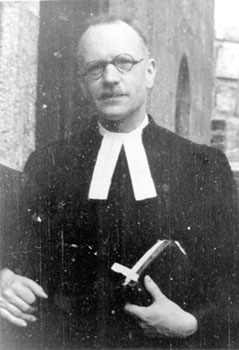

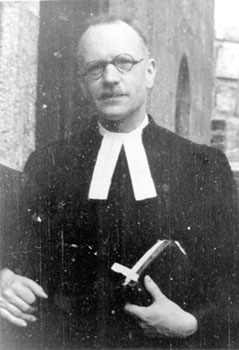

The citizens of Le Chambon and André and Magda Trocmé: Le Chambon is a remote mountain plateau in south-eastern France, where people in many villages sheltered Jews from deportation and en route to escape to Switzerland.

The citizens of Le Chambon and André and Magda Trocmé: Le Chambon is a remote mountain plateau in south-eastern France, where people in many villages sheltered Jews from deportation and en route to escape to Switzerland.

When the deportations began in France in 1942, Trocmé

, the local pastor, urged his congregation in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (S.E.France) to give shelter to any Jew who should ask for it. The village and its outlying areas were quickly filled with hundreds of Jews. Some of them found permanent shelter in the hilly region of Le Chambon, and others were given temporary asylum until they were able to escape across the border, mostly to Switzerland. Jews were housed with local townspeople and farmers, in public institutions and children’s homes. With the help of the inhabitants some Jews were then taken on dangerous treks to the Swiss border. The entire community banded together to rescue Jews, viewing it as their Christian obligation. Yad Vashem https://www.yadvashem.org/righteous/stories/trocme.html

, the local pastor, urged his congregation in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (S.E.France) to give shelter to any Jew who should ask for it. The village and its outlying areas were quickly filled with hundreds of Jews. Some of them found permanent shelter in the hilly region of Le Chambon, and others were given temporary asylum until they were able to escape across the border, mostly to Switzerland. Jews were housed with local townspeople and farmers, in public institutions and children’s homes. With the help of the inhabitants some Jews were then taken on dangerous treks to the Swiss border. The entire community banded together to rescue Jews, viewing it as their Christian obligation. Yad Vashem https://www.yadvashem.org/righteous/stories/trocme.html

“We do not know what a Jew is. We only know men”, he said when asked by the Vichy authorities to produce a list of the Jews in the town. Hallie, 1979, p103

Trocmé urged his congregants to “do the will of God, not of men,” and stressed the importance of fulfilling the commandment in Deuteronomy 19:2-10 concerning the entitlement of the persecuted to shelter. Yad Vashem

I won’t go into the story of Oskar Schindler right here. The story is well-known and the book Schindler’s Ark, and the film Schindler’s List give lots of detail. I’ll discuss him later.

I won’t go into the story of Oskar Schindler right here. The story is well-known and the book Schindler’s Ark, and the film Schindler’s List give lots of detail. I’ll discuss him later.

There are many more stories. The Yad Vashem Foundation instituted an award Righteous Among the Nations, for non-Jews who had rescued Jews during the Holocaust.

“In a world of total moral collapse there was a small minority who mustered extraordinary courage to uphold human values. These were the Righteous Among the Nations […] Contrary to the general trend, these rescuers regarded the Jews as fellow human beings who came within the bounds of their universe of obligation.” Yad Vashem Foundation

You can probably think of many well-known cases that might qualify: Paul Grüninger, Oskar Schindler, Chiune Sugihara, Raoul Wallenberg – but how many were there in total?

What would you think, given that in most of those times, in many of those places, helping Jews in any way was at least illegal, and in many cases could lead to being immediately killed or tortured. A dozen, a hundred, a few hundred, a few thousand?

My initial guess was several hundred or a few thousand. When I checked I found that by 1 January 2019, Yad Vashem had recognized over 27,000 Righteous Among the Nations from 51 countries.

So many. Not enough, obviously, but this kind of resistance is something that many people will rise to, if necessary.

Vietnam War: In the midst of the atrocities of war, there are always those who resist. In 1968, during the Vietnam War, there was a massacre in the village of My Lai, during which American soldiers spent hours killing, raping and mutilating between 300 and 500 defenceless civilians of all ages. You can easily find horrible details of this, so I won’t spell them out here. Amongst the soldiers on the ground, there were those who refused orders to shoot people. Here is an account from Harry Stanley:

Lt Calley ordered [me] to shoot these people and I refused, and he told me he was going to court-martial me when we got back to base camp, and I told him what was on my mind at the time. Ordering me to shoot down innocent people: that’s not an order, that’s craziness to me. I don’t feel I have to obey that. If you want to court-martial me you do that if you think you can get away with it. […] It was immoral to me.

You can see this brief interview Harry Stanley at 6:07 onwards at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Ap96BUJgz4 This, and the clip with Hugh Thompson (below), are from the Yorkshire Television documentary Four Hours at My Lai. There are many horrible things in this programme, but the interviews with Stanley and Thompson are not horrible.

Hugh Thompson, a helicopter pilot who was flying cover for the troops on the ground, started to realise that something had gone wrong.

Hugh Thompson, a helicopter pilot who was flying cover for the troops on the ground, started to realise that something had gone wrong.

During the mission as it was going on, we kept just reconning around: started seeing a lot of bodies. It didn’t add up, you know, how people were getting killed and wounded, and we weren’t receiving any fire – just didn’t make sense: there was too many casualties and how they were – the locations they were in – y’know, figured our artillery couldn’t do this – bodies in places the artillery didn’t hit – trying to get out of the village.

He landed his helicopter, and found a group of soldiers advancing on a group of women and children. Larry Coburn, Thompson’s door gunner:

“Warrant Officer Thompson was desperate to get these civilians – what he believed to be civilians – out of this bunker and into a safe area. He’s seen beforehand that what he was trying to do to help the people on the ground wasn’t getting done. He was convinced that the ground forces would kill these people if he couldn’t get to them first. He landed the aircraft between the American forces and the Vietnamese people in the bunker, got out of the aircraft, had us get out of the aircraft with our weapons to cover him, and he went and had words with the Lieutenant on the ground. He asked the Lieutenant how he could get these people out of the bunker. The Lieutenant said the only way he knew was with hand grenades, so when Warrant Officer Thompson came back to the aircraft he was furious, and he was desperate to get these people out of the bunker himself. […] He told us if the Americans were to open fire on these Vietnamese as he was getting them out of the bunker that we should return fire – on the Americans”.

Hugh Thompson: “When I did instruct my crew – my crew chief and gunner – y’know, to open up on them if they opened up on any more civilians, I don’t know how I would have felt if they had opened up on them, but that particular day I wouldn’t have given it a second thought. They were the enemy at that time, I guess”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iA4MFdDqpr4 1:34 to 4:50

Thompson and his crew recruited help from other helicopters, and airlifted over a dozen civilians to safety. Thompson was unpopular as a result of his actions. On later missions, his crew member Glenn Andreotta was killed, and Thompson broke his back in a crash. His actions were sharply criticised by some back in the States. Democrat Congressman Mendel Rivers publicly stated that he felt Thompson was the only soldier at My Lai who should be punished (for turning his weapons on fellow American troops) and unsuccessfully attempted to have him court-martialled.

Eventually, Hugh Thompson was awarded the Soldier’s Medal in 1998, thirty years after his actions.

“The Soldier’s Medal is awarded to any person of the Armed Forces of the United States or of a friendly foreign nation who, while serving in any capacity with the Army of the United States, distinguished himself or herself by heroism not involving actual conflict with an enemy.”

Characteristically, he initially refused to accept the medal, unless Glenn Andreotta and Lawrence Colburn, his crew members, both received the same honour.

If you want to follow up more on My Lai, it’s worth finding out about those who played a heroic role in uncovering the massacre, such as Ron Ridenhour and Ron Haeberle.

Palo Alto, California 1971: The Stanford Prison Experiment

This was Philip Zimbardo’s ‘fake prison’ study, in which randomly assigned student ‘guards’ bullied and abused other students who were acting as ‘prisoners’. The accounts of the experiment usually say something like ‘after six days, because of the escalating abuse by the guards ,the experiment was terminated’, which gives the impression that Zimbardo made the decision. However, Zimbardo makes it clear in his book (Zimbardo, 2007) that the initiative came from Christina Maslach, and that he initially opposed her. Maslach was going out with Zimbardo at the time, and he had invited her down to the study site to see all the fascinating stuff that was going on. She was appalled, and directed him to stop the study straight away.

“…I challenged whether she could ever be a good researcher if she was going to get so emotional from a research procedure. I told her that dozens of people had come down to this prison and no one had reacted as she had. She was furious. She didn’t care if everyone in the world thought what I was doing was OK. It was simply wrong. Boys were suffering. As principal investigator, I was personally responsible for their suffering. They were not prisoners, not experimental subjects, but boys, young men, who were being dehumanised and humiliated by other boys who had lost their moral compass in this situation.” Zimbardo, 2007, p170

Maslach was a research student at the time, and Zimbardo was a faculty member, so her opposition was risky to her in a number of ways.

Maslach recalls: “…a bit of a tirade by Phil (and other staff there) about what was the matter with me. Here was fascinating human behaviour unfolding, and I, as a psychologist, couldn’t even look at it? They couldn’t believe my reaction, which they may have taken to be a lack of interest. Their comments and teasing made me feel sick and stupid – the out-of-place woman in this male world – in addition to already feeling sick to my stomach by the sight of these sad boys so totally dehumanised.” Zimbardo, 2007, pp170-171

In fact Zimbardo reluctantly accepted her judgement and stopped the experiment. “At the time it was a slap in my face, the wake-up call from the nightmare that I had been living” p170. (They later married, and are still married, almost 50 years later, happily as far as I know. This is pretty good going for academics.)

Iraq: Abu Ghraib Prison 2004: There was systematic mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners by a small group of American Army prison guards. You have probably seen the photographs. This is often portrayed as being just like the Stanford Prison Experiment. (My interpretation of the SPE is very different from the standard textbook one, and it’s clear from Zimbardo’s (2007) detailed account that the standard version of what happened, let alone the psychological interpretation, is inaccurate. I think that both Stanford and Abu Ghraib show how lax management and a generally malign environment allow dominant individuals with bullying tendencies to emerge and control the abuse. But that’s for another lecture.)

Sergeant Joe Darby, a military policeman at the prison, was given a CD with lots of photos of Iraq by Chuck Graner, one of the abusers, so he could pick some to send home to his family. Amongst the city scenes and sunsets, he discovered the now well-known photos of the physical and sexual abuse of the prisoners by Graner and other members of the 372nd Military Police Company. Darby sat on the photos for several weeks, and initially tried to expose this abuse anonymously, because he knew it would be dangerous for him to blow the whistle on it.

Darby didn’t do anything in a hurry. ‘I’d been in the military and around a lot of these guys long enough to know we take care of our own,’ he said. He anticipated what would be said if he reported the pictures: ‘That I was turning in my friends, that I was a traitor, that I was a stool pigeon.’ […] ‘Is it going to be worth the possible retaliation?’ Gourevich & Morris 2008, pp235-236

In the end, he handed the pictures to the army CID. He was right about possible consequences. The identity of the whistle-blower was kept secret in Iraq, but Donald Rumsfeld, the US Defence Secretary, named him in a congress committee. Darby was immediately smuggled back to the states for his own safety. There were repercussions for his family, too:

His wife had no idea that Mr Darby had handed in those photos, but when he was named, she had to flee to her sister’s house which was then vandalised with graffiti. Many in his home town called him a traitor. That animosity in his home town has meant that he still cannot return there…… …After Donald Rumsfeld blew his cover, he was bundled out of Iraq very quickly and lived under armed protection for the first six months…… …Mr Darby and his family have moved to a new town. They have new jobs. They have done everything but change their identities.

Bryan (BBC News August 2007)

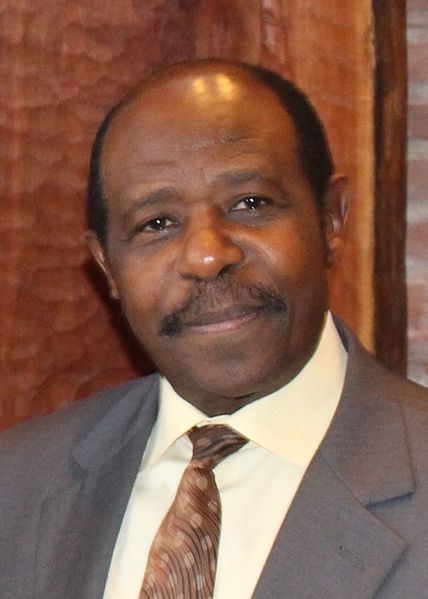

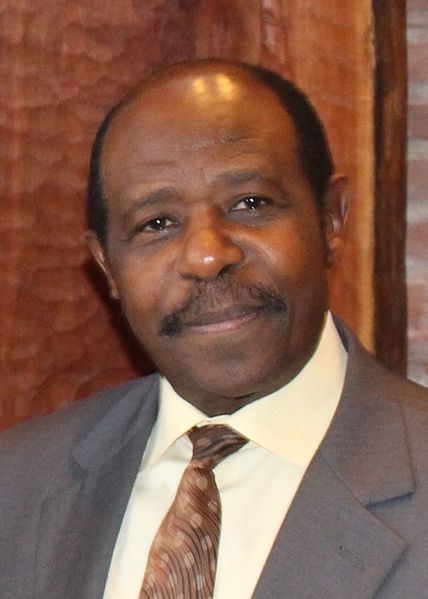

Rwanda 1994: During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Paul Rusesabagina used his influence and connections as temporary manager of the Mille Collines hotel to shelter 1,268 Tutsis and moderate Hutus for several months from being slaughtered by the Interahamwe militia.

Rwanda 1994: During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Paul Rusesabagina used his influence and connections as temporary manager of the Mille Collines hotel to shelter 1,268 Tutsis and moderate Hutus for several months from being slaughtered by the Interahamwe militia.

Rusesabagina’s story is well-known and well-documented, including in his own book An Ordinary Man (2007), and in the film Hotel Rwanda (2004).

I’ll discuss him in more detail later.

A psychology of Doing the Right Thing

So, lots of cases. What is the psychology of all this? There isn’t a simple answer, and there’s not very much research. I’ll discuss that, and then make some suggestions based on the examples I’ve described so far.

Milgram has an appendix on ‘patterns among individuals’ in his book, which discusses the characteristics of those who resisted, but found but found few consistent similarities in them.

In any event it would be a mistake to believe that any single temperamental quality is associated with disobedience or to make the simple-minded statement that kindly and good persons disobey, while those who are cruel do not. There are simply too many points in the processes at hand at which various components of the personality can play complicated roles to allow any oversimplified generalisations Milgram, 1974, p226

Milgram’s study is difficult to replicate, for ethical reasons, but there have been further analyses of his archives, and versions with less damaging ‘punishments’ which have been run, which suggest some consistencies. Stephen Gibson did a rhetorical analysis of transcripts from Milgram’s studies.

“Analysis draws attention to the way in which participants could draw the experimenter into a process of negotiation over the continuation of the experimental session, something which could lead to quite radical departures from the standardized experimental procedure.” Gibson, 2013, p290

Modigliani & Rochat (1995) analysed film and audio recordings of 36 respondents in the version of the Milgram study which was conducted in an office building in Bridgeport, rather than at Yale, where the obedience rate was 47%. They hypothesized that “The sooner in the course of the experiment a subject begins to show notable resistance, the more likely he will be to end up defiant.” p107. After analysis they concluded “the lower the voltage at which subjects first question, object, or refuse, the lower will be the final voltage they will deliver.” p117, original emphasis.

Both of these factors show the dynamic nature of agreeing to cooperate with evil, as Milgram did in stressing the importance of the gradual escalation of the level of shock in his original design. They point out the importance of quickly grasping what is going on, and of having the verbal and social skills to negotiate with the malign authority, both of which will crop up in later discussion.

Morselli and Passini (2010) analysed autobiographies by Gandhi, Mandela and Martin Luther King. They found that all three report the influence of parents: ‘a very strong and self-confident person’ (King); ‘incorruptible and had earned a name for strict impartiality’ (Ghandi); ‘My father possessed a proud rebelliousness,, a stubborn sense of fairness that I recognise in myself (Mandela). All three recalled how encounters with new social contexts, peoples and ideas in adolescence affected their relationship with authority, and all three stressed the importance of social relationships and a supportive social context in dealing with the hardship and persecution that resulted from resisting authority.

Philip Zimbardo recorded a long interview about his Hero Construction Company project in 2012, already referred to. It is available at http://vimeo.com/40425064. In this part of my lecture I used the section from 10:40 to 14:35. It’s actually an hour-ling interview and discussion. This is the summary of the points he makes there.

He differentiates heroism from altruism because those who do it are aware of the personal cost and risk. There are three kinds of heroes

- The impulsive, reactive hero: the person who perceives an emergency and reacts immediately. He gives the example of Wesley Autrey, who dived onto a subway track, in the face of an oncoming train, to save someone who had fallen on the tracks.

- The reflective, proactive hero: these are the whistleblowers. They see something immoral and they often have to collect sufficient data to present to authority, they have to get people to support them, other people on their side

- A third kind, whose whole life is focussed on a cause: examples like Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Mother Theresa

These categories don’t fit clearly with the examples I’ve given above. Perhaps Hugh Thompson and Christina Maslach as impulsive and reactive, but the other examples seem to have elements beyond the categories above.

What’s the difference between them in terms of psychology? Zimbardo’s conclusion in the interview is that “we don’t have a clue.” Milgram reached a similar conclusion about disobedience:

My overall reaction was to wonder at how few correlates there were of obedience and disobedience and how weakly they are related to observed behaviour. I am certain that there is a complex personality basis to obedience and disobedience. But I know we have not found it. In any event it would be a mistake to believe that any single temperamental quality is associated with disobedience, or to make the simple-minded statement that kindly and good persons disobey while those who are cruel do not. Milgram 1974 p226

However, in the last chapter of The Lucifer Effect (Zimbardo, 2007), and on his website, Zimbardo does suggest some characteristics of those who are successful in resisting evil:

- Mindfulness

- Hardiness/accepting interpersonal conflict

- Extended time-horizon

- Resist rationalising inaction

- Transcend anticipating negative consequences

Those are rather dense terms, and it’s worth simplifying them a bit.

Mindfulness: this isn’t the meditation stuff. It’s to do with clearly realising what’s going on, what the implications and consequences might be – and not being sucked into doing something inhumane without paying attention to it. It also applies to not being the kind of person who ignores injustice if it doesn’t affect them.

Hardiness/accepting interpersonal conflict: being prepared to accept disagreement, being unpopular, not being accepted if you stand up for what you think is right. This is pretty obvious in those who refuse to go along with bullying peer groups.

Extended time-horizon: thinking about future consequences, both for possible victims, but also for yourself. ‘If I walk away now, it’ll be easier for me right now, but I’ll regret it for the rest of my life.’

Resist rationalising inaction: don’t be led astray by thinking ‘there’s no point doing anything – it won’t make any difference’; ‘it’s not my responsibility’; ‘other people can intervene more effectively than me’. The traditional challenge: ‘if not you, who? If not now, when?’ is an encouragement to ‘resist rationalising inaction’.

Transcend anticipating negative consequences: Being prepared to accept that this might turn out badly for you – but being prepared to do it anyway, because it’s the right thing to do. This is a tough thing to do.

Two of the people from my examples have recorded statements about their motivation. Read through these, and see if they fit with Zimbardo’s categories.

The first is from The Making of Hotel Rwanda (George 2004) in ‘additional material’ on the DVD of the film Hotel Rwanda, about Paul Rusesabagina.

Rusesabagina: I didn’t have any other motivation. I just took in people. I helped them. I was willing to do it, and I really didn’t have time to think about all that… Because it took every second, every minute, every day, seven days a week, and I had to work very hard, and very fast, always to avoid the disaster.

Of course, at a certain given time, I knew I was going to be killed. But I didn’t take it that way. I thought that – dying: one day, we’ll all die – but, at least, dying without doing anything, to me, was a failure. That was why I had to fight up to the end.

Don Cheadle, who played Rusesabagina in the film: It was as selfish an act to him as it was a selfless act, in that he could not have lived with himself, and he could not, you know, have looked in the mirror and gone on, knowing that he had left however many it was in his care at the hotel to perish, at a time when he felt that he could have done more.

Paul Rusesabagina: I took it as an obligation, to help my neighbour – whether I know him or not. Because, even if I do not know someone, why should he or she die? Why should she be killed? Is there any reason to take out somebody’s life?

Terry George, Director: When I listen to him talk and people ask him does he consider himself a hero, and he says “No, I’m an ordinary man: that was my job to do that. That’s what I had to do” and I think that’s the strength of Paul, the inner moral courage, the desire to help the ordinary man, is the strength of the character.

Then this is Joe Darby talking about why he revealed the Abu Ghraib photographs, from ‘additional scenes’ on the DVD of Standard Operating Procedure (Morris, 2008)

Joe Darby: I felt it was not only the right thing to do, but it was my job. I was my duty as an MP [Military Police] to do this, and I’ve never felt anything more than I was just an MP doing my job. My job in the army was to put people in prison for doing wrong, and that’s what I did. I would have been very, very happy if these people had been put in prison and it had ended there […]

I didn’t want it to become national news. I didn’t want to be labelled a hero or a traitor. I didn’t want people to know who I was. I just wanted people punished for the wrong they had done.

I don’t see myself as a hero or a traitor. I see myself as an MP who did his job and punished those who had broken the law. It was my burden to bear and, you know, I had to do it.

The resisters from My Lai show signs of ‘transcending anticipating negative consequences’. Harry Stanley: “If you want to court-martial me you do that, if you think you can get away with it.” Hugh Thompson: “I don’t know how I would have felt if they had opened up on them, but that particular day I wouldn’t have given it a second thought.”

Bocchiaro & Zimbardo (2010) ran a variant of Milgram’s procedure (in which respondents were urged to give ‘learners’ insults instead of electric shocks). They found 60% refusers.

“To assess possible individual differences between disobedient and obedient participants, we compared the scores they obtained on BFQ [the Big Five Questionnaire]. No statistically significant differences were found on any of the five BFQ dimensions nor any of the 10 sub-dimensions.” p163 (added emphasis).

None of them thought that this behaviour was unusual or extraordinary. […] They believed they made a most obvious decision at that time in the experiment. Among the most common answers were “I think everyone would have done the same”. pp164-165

Another perspective

The examples I have given seem to show admirable characteristics like mindfulness, farsightedness, and courage, but there are also other factors which are not in themselves noble, or might not be seen as desirable in other circumstances. It’s possible that some of these admirable people would not be ones that you would choose as friends, or be comfortable working with. Some of them are people who chose to go against what was seen as right and reasonable in their society at that particular time, and they might not seem generally right-minded and reasonable people. Many of them broke the law in their actions, and those who are accustomed to breaking the law in other ways may find it easy to do, and be skilled at doing it, when the law turns out to be malign.

For instance, to maintain resistance in a hostile, dynamic environment, you need quick-wittedness, and social skill, to the extent of being the kind of person who can manipulate situations and persons to your own advantage. Schindler and Rusesabagina show this.

Oskar Schindler:

Because of his good business contacts, his conviviality, his gifts of salesmanship, his ability to hold drink, he had got a job even in the midst of the depression as sales manager of Moravian Electrotechnic. Keneally 1982 Schindler’s Ark p28

Johnathan Dresner: “He was an adventurer. He was like an actor who always wanted to be centre stage. He got into a play, and he couldn’t get out of it.”

Mosche Bejski: “Schindler was a drunkard. Schindler was a womanizer. His relations with his wife were bad. He often had not one but several girlfriends. After the war, he was quite unable to run a normal business. During the war, as long as he could produce kitchenware and sell it on the black market and make a lot of money, he could do it. But he was unable to work normally, to calculate normally, to hold down a normal job, even in Germany. […Everything he did put him in jeopardy. You had to take him as he was. Schindler was a very complex person. Schindler was a good human being. He was against evil. He acted spontaneously. He was adventurous, someone who took risks, but I’m not sure he enjoyed taking them … He was very, very sensitive. If Schindler had been a normal man, he would not have done what he did.” Silver, 1992, p147-148.

On the other hand, when

…two Gestapo men came to his office and demanded that he handed over a family of five who had bought forged Polish identity papers ‘Three hours after they waked in’ Schindler told the writer Kurt Grossman, ‘two drunken Gestapo men reeled out of my office without their prisoners and without the incrimination documents they had demanded.’. Silver, 1992, p149

‘I don’t know why he did it,’ they say. ‘Oskar was a gambler, was a sentimentalist who loved the transparency, the simplicity of doing good; that Oscar was an anarchist who loved to ridicule the system, and that beneath the hearty sensuality lay a capacity to be outraged by human savagery, to react to it, and not to be overwhelmed.'” Keneally, 1982, p278

Paul Rusesabigina, an assistant manager of a luxury hotel in the capital city of a poor country, recounts that he was familiar with corruption and manipulation in better times

They gave me an office of my own, as well as the authority to dispense little perks here and there to favoured guests. An Army general who came infrequently would get a free cognac, or perhaps a lobster dinner. It made them feel appreciated, which is a universal hunger among all human beings. p58

I took my morning coffee at the bar, watched the comings and goings, made careful note of who the regulars were, followed the gossip about their careers, and saved up that knowledge for the frequent times when I would find myself clinking glasses of complimentary Merlot with a man whose friendship was another link to the power web of the capital and whose favour I could count on in the future. And the presence of beverages always kept the tone easy and social, even when the subtext of the discussion was quite serious. Rusesabagina, 2007, pp64-65

He used those skills to good effect later.

Today I am convinced that the only thing that saved those 1,268 people in my hotel was words. Not the liquor, not money, not the UN. Just ordinary words directed against the darkness, I used words in many ways during the genocide – to plead, intimidate, coax, cajole, and negotiate. I was slippery and evasive when I needed to be. I acted friendly towards despicable people. I put cartons of champagne in their car trunks. I flattered them shamelessly.

I said whatever I thought it would take to keep the people in my hotel from being killed. I had no cause to advance, no ideology to promote beyond that one simple goal. Rusesabagina, 2007, p xvii

So as well as mindfulness, farsightedness, courage, quick-wittedness and social skill, manipulativeness and readiness to break the rules may be important. Alternatively, however, an unusual determination to follow rules and principles, unreasonable insensitivity to social niceties, and overwhelming confidence in one’s own judgement might be helpful. After all, these people may be completely rejecting what is currently seen as sensible and right behaviour, and may be inconveniencing or endangering their friends and neighbours, as well as rejecting their neighbours’ views about the oppressed. These characteristics may be associated with some degree of autism. Attwood (2020) notes that those with autism are usually renowned for being direct, speaking their mind, and being honest and determined and having a strong sense of social justice. They may show remarkable honesty, and delay in the development of the art of persuasion, compromise and conflict resolution.

Moorehead (2014) comments on André and Magda Trocmé, the church couple who were important in encouraging the villagers to shelter Jews in Le chambon. “…they were also complicated, overbearing and strong.” p112; “Somewhat similar in temperament, both impatient, short-tempered, outspoken, highly-educated and apparently sure of themselves…” p114; “A colleague observed that Trocmé possessed an openness and a courage ‘unusual, alas, in our churches’, and that he had rarely met a Christian ‘so little frightened of the consequences of clarity’.” p115

A New York Times account of Sherron Watkins, who was the whistleblower who exposed the massive frauds in the Enron Corporation, describes similar characteristics:

In the cutthroat business culture of the Enron Corporation, where toughness and a sharp tongue were often prerequisites for success, Sherron S. Watkins could be noticeably tough and sharp.

One former colleague described her as ”a bull in the china shop” at times. Others mistook the Texan Ms. Watkins for a brusque New Yorker. But several former colleagues agreed that her toughness was rooted in a strong sense of business ethics and that she was unafraid to deliver difficult news, even to her superiors.

”In my experience, she was not afraid to speak the truth, even when it was uncomfortable,” said Stephen Schwarz, a former Enron employee who worked with Ms. Watkins, Yardley, 2002

Watkins herself describes her dependence on her Christian faith, and the importance of taking guidance from the Scriptures literally:

It was an unsettling time, the morning after the disclosure, I woke to camera crews surrounding our house. My hands were shaking, I was so nervous about the situation. I picked up my Bible and opened by chance to Hebrews 12. The first 3 verses say,

“Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles, and let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us. Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy set before him, endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God. Consider him who endured such opposition from sinful men, so that you will not grow weary and lose heart.” http://www.sherronwatkins.com/sherronwatkins/My_Passion.html (no longer available)

Although her actions are different from those of the people described here, Greta Thunberg is also someone who is prepared to take a stand against general indifference to a major problem. She sees her autism as a help in her actions.

I just know what is right and I want to do what is right. I want to make sure that I do everything in my power to stop this crisis from happening. I have Asperger’s – I’m on the autism spectrum – so I don’t really care about social codes. [..] It makes you different, it makes you think differently, and especially in such a big crisis as this, when you need to think outside the box. Interview with CBS This Morning, 2019

Everyone else is “OK, it’s very important, but I am too busy with my life…”, and I just thought it was very strange that no-one else was behaving in a logical way. What would the logical way be? To do something; to step out of your comfort zone. Interview with Democracy Now! 2019

I have heard a quote from Thunberg in which she says explicitly that neurotypical people are able to think ‘something must be done’, and ‘things can carry on as normal’ at the same time, but her condition means that it is literally impossible for her to do that – and that’s why her condition has given her the power to do what she’s done – but I can’t find it to give you the precise source.

The banality of good action

On the other hand, it may be possible to establish an environment which promotes the banality of heroism. Rochat & Modigliani (1995) comment on the villagers of Le Chambon:

Almost all of those involved in the effort at Le Chambon had not plotted in advance to counter the Vichy Government. Only gradually did they arrive at a path that flatly opposed the government’s policies and actions regarding refugees and Jews.

[…] In effect, they established an orientation of civility and kindness toward persecuted people and they proceeded to maintain this stance after it was officially outlawed by the authorities.

[…] They did one thing at a time, and one thing after the other, each move bringing them closer to becoming the rescuers we admire today. pp201-205

This is a passing point in this essay, which is worth developing more, perhaps in the context of Zimbardo’s account of the situational factors which encourage evil behaviour, which I mention in the next section.

Heroes

All cultures know about heroes, and traditional/mythical tales of heroes often describe their motivations. Franco & Zimbardo (2006), describe this as:

“…a code of conduct served as the framework from which heroic action emerged. In this code, the hero follows a set of rules that serves as a reminder, sometimes even when he would prefer to forget, that something is wrong and that he must attempt to set it right.” p35

My examples sometimes echo that. Harry Stanley: “It was just immoral to me”; Joe Darby: “My job in the army was to put people in prison for doing wrong, and that’s what I did […] It was my burden to bear and, you know, I had to do it.”

But Zimbardo also points out that Great Heroes are not a very useful example for most people. Almost by definition, they do stuff we can’t or wouldn’t do. Everyday heroes are better examples – and maybe ‘heroes’ isn’t the right word: People who do the right thing. It’s possible that there are many of those around.

Zimbardo, Breckenridge & Moghaddam, (2013) asked a nationally representative sample of 4000 participants from the general public in the United States “Have you ever done something that other people – not necessarily you yourself – considered a heroic act or deed?” 20% said yes. Among those:

55% had helped someone during an emergency,

8% confronted an injustice,

14% had defied unjust authority, and

5% had sacrificed for a stranger (organ donation or similar).

In this study, both blacks and Hispanics were twice as likely as whites to have performed heroic deeds. Zimbardo & al suggest that in contrast to an “exclusive” vision of heroism, which presents heroic leadership by exceptional individuals, an “inclusive” vision depicts heroism as integral to everyday life for ordinary people, and widespread volunteer participation in social life as normative in all democracies. The occasions people recalled may have been trivial compared with the actions of the Righteous Among the Nations, but both examples are encouraging.

General social support for right actions, even if it isn’t very strident, may also help individuals in doing the right thing. Grüninger said about his law-breaking; “we were guided also by the opinion of a large portion of the Swiss people, of the press, and

of the political parties” (Rochat & Modigliani, 2000, p99), and Gandhi, M.L. King, and Mandela all stressed the importance of support from others in their autobiographies.

Zimbardo is still convinced of the importance of the social environment in promoting good or bad behaviour.

…there are no special attributes of either pathology or goodness residing within the human psyche or the human genome. Both conditions emerge in particular situations at particular times when situational forces play a compelling role in moving particular individuals across a dividing line from inaction to action. There is a decisive decisional moment when a person is caught up in a vector of forces that emanate from a behavioural context. These forces combine to increase the probability of one’s acting to harm others or acting to help others.”

[…] Among the situational action vectors [for evil behaviour] are group pressures and group identity, the diffusion of responsibility for the action, a temporal focus on the immediate moment without concern for consequences stemming from the act in the future, presence of social models, and commitment to an ideology. Zimbardo (2007), pp485-486 (emphasis added)

These factors can act to promote evil behaviour, but there is always the possibility turning them round to promote good. It’s worth noting that Christina Maslach has pointed out that refusing to obey malign orders, or resisting oppression isn’t enough: people need to do something to stop it – as she did at Stanford.

What would I like to be the takeaway messages from this piece?

In response to the oversimplified accounts of the psychology of obedience and conformity, based on the work of people like Milgram and Zimbardo fifty years ago, we should remember:

- People aren’t always obedient to authority

- It isn’t inevitable that they follow the roles prescribed

- There are other things you can do.

- It’s important to study those who take the other path.

Resistant participants in Milgram’s study: Paul Grüninger; Oskar Schindler; Irena Sendlerowa; Hugh Thompson; Harry Stanley; Chris Maslach; Joe Darby; Paul Rusesabagina – and countless others. These are people who deserve our respect, but they are also people who deserve further psychological study, to hep to develop a psychology of Doing The Right Thing.

References

Attwood, Tony (2020) What is Aspergers https://www.tonyattwood.com.au/about-aspergers/what-is-aspergers Accessed 13 March 2020

Bocchiaro, Piero, Zimbardo, Philip (2010) Defying Unjust Authority: An exploratory study Current Psychology 29, 155-170

Bryan, Dawn (BBC News August 2007) Abu Ghraib whistleblower’s ordeal Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/6930197.stm Accessed 14 March 2020

Franco, Zeno & Zimbardo, Philip (2006) The Banality of Heroism Greater Good Fall/Winter 2006/7, 30-35 Available online at http://www.lucifereffect.com/articles/heroism.pdf

Gibson, Stephen (2013) Milgram’s Obedience Experiments: A Rhetorical Analysis British Journal of Social Psychology 52, 290-309

George, Terry (2004) Additional Material Hotel Rwanda DVD

Gourevitch, Philip and Errol Morris (2008) Standard Operating Procedure London: Picador

Hallie, Philip (1979), Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed: The Story of Le Chambon and How Goodness Happened There New York: Harper & Row

Milgram, Stanley (1974) Obedience to Authority NY: HarperCollins

Modigliani, Andre & Rochat, François (1995) The Role of Interaction Sequences and the Timing of Resistance in Shaping Obedience and Defiance to Authority Journal of Social Issues 51(3), 107-123

Morehead, Caroline (2014) Village of Secrets: defying the Nazis in Vichy France London: Vintage

Morselli, Davide and Passini, Stefano (2010) Avoiding Crimes of Obedience: A Comparative Study of the Autobiographies of M.K. Ghandi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King, Jr Peace and Conflict; Journal of Peace Psychology, 16, 295-319

Rochat, François & Andre Modigliani (2000) Captain Paul Grueninger: The Chief of Police Who Saved Jewish Refugees by Refusing to Do His Duty in Thomas Blass Obedience to Authority: Current Perspectives on the Milgram Paradigm Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Rusesabagina, Paul (2007) An Ordinary Man: The True Story Behind Hotel Rwanda London: Bloomsbury

Silver, Eric (1992) The Book of the Just New York; Grove Press

Still, William (2017) The Underground Railroad London: Arcturus Publishing (first published 1872)

Van Emden, Richard (2007). The Last Fighting Tommy: The Life of Harry Patch, the Oldest Surviving Veteran of the Trenches. London: Bloomsbury

Yardley, Jim (2002) Enron’s Collapse: the Employee; Author of Letter To Enron Chief Is Called Tough New York Times, Jan 16, 2002 https://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/16/us/enron-s-collapse-the-employee-author-of-letter-to-enron-chief-is-called-tough.html

Zimbardo, Philip (2007a) The Lucifer Effect London: Rider

Zimbardo, Philip (2007b) Resisting Social Influences and Celebrating Heroism (chapter 16) in The Lucifer Effect London: Rider

Zimbardo, Philip (2012) talking about his Heroic Imagination Project: http://vimeo.com/40425064

Zimbardo,P.G., Breckenridge,J.N. & Moghaddam,F.M. (2013) “Exclusive” and “Inclusive” Visions of Heroism and Democracy. Curr Psychol 32, 221–233

World War One: Not all soldiers are prepared to follow orders to kill. Harry Patch was one of the longest-surviving soldiers from World War One. He was a member of a machine-gun team, a main mechanism for delivering death, but he wrote in his memoir:

World War One: Not all soldiers are prepared to follow orders to kill. Harry Patch was one of the longest-surviving soldiers from World War One. He was a member of a machine-gun team, a main mechanism for delivering death, but he wrote in his memoir: Early stages of the Holocaust: Paul Grüninger (Paul Groeninger in some English-language versions), was a Chief of Police on part of the Swiss border with Austria in 1938-39. After the Nazi occupation of Austria in March, 1938, the Swiss government decided to prevent the movement into Switzerland of Jewish refugees. They cited concerns about the risks of ‘overload’ of refugees/asylum seekers, foreigners who would have difficulty integrating. There was fear of foreign ‘overpopulation’ in a small country. Refugees were depicted as ‘rejects, the dregs of society’.

Early stages of the Holocaust: Paul Grüninger (Paul Groeninger in some English-language versions), was a Chief of Police on part of the Swiss border with Austria in 1938-39. After the Nazi occupation of Austria in March, 1938, the Swiss government decided to prevent the movement into Switzerland of Jewish refugees. They cited concerns about the risks of ‘overload’ of refugees/asylum seekers, foreigners who would have difficulty integrating. There was fear of foreign ‘overpopulation’ in a small country. Refugees were depicted as ‘rejects, the dregs of society’. Later: From 1935 to 1943 Irena Sendler or Irena Sendlerowa worked for the Department of Social Welfare and Public Health of the City of Warsaw.

Later: From 1935 to 1943 Irena Sendler or Irena Sendlerowa worked for the Department of Social Welfare and Public Health of the City of Warsaw. The citizens of Le Chambon and André and Magda Trocmé: Le Chambon is a remote mountain plateau in south-eastern France, where people in many villages sheltered Jews from deportation and en route to escape to Switzerland.

The citizens of Le Chambon and André and Magda Trocmé: Le Chambon is a remote mountain plateau in south-eastern France, where people in many villages sheltered Jews from deportation and en route to escape to Switzerland. , the local pastor, urged his congregation in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (S.E.France) to give shelter to any Jew who should ask for it. The village and its outlying areas were quickly filled with hundreds of Jews. Some of them found permanent shelter in the hilly region of Le Chambon, and others were given temporary asylum until they were able to escape across the border, mostly to Switzerland. Jews were housed with local townspeople and farmers, in public institutions and children’s homes. With the help of the inhabitants some Jews were then taken on dangerous treks to the Swiss border. The entire community banded together to rescue Jews, viewing it as their Christian obligation. Yad Vashem

, the local pastor, urged his congregation in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (S.E.France) to give shelter to any Jew who should ask for it. The village and its outlying areas were quickly filled with hundreds of Jews. Some of them found permanent shelter in the hilly region of Le Chambon, and others were given temporary asylum until they were able to escape across the border, mostly to Switzerland. Jews were housed with local townspeople and farmers, in public institutions and children’s homes. With the help of the inhabitants some Jews were then taken on dangerous treks to the Swiss border. The entire community banded together to rescue Jews, viewing it as their Christian obligation. Yad Vashem  I won’t go into the story of Oskar Schindler right here. The story is well-known and the book Schindler’s Ark, and the film Schindler’s List give lots of detail. I’ll discuss him later.

I won’t go into the story of Oskar Schindler right here. The story is well-known and the book Schindler’s Ark, and the film Schindler’s List give lots of detail. I’ll discuss him later. Hugh Thompson, a helicopter pilot who was flying cover for the troops on the ground, started to realise that something had gone wrong.

Hugh Thompson, a helicopter pilot who was flying cover for the troops on the ground, started to realise that something had gone wrong. Rwanda 1994: During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Paul Rusesabagina used his influence and connections as temporary manager of the Mille Collines hotel to shelter 1,268 Tutsis and moderate Hutus for several months from being slaughtered by the Interahamwe militia.

Rwanda 1994: During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Paul Rusesabagina used his influence and connections as temporary manager of the Mille Collines hotel to shelter 1,268 Tutsis and moderate Hutus for several months from being slaughtered by the Interahamwe militia.